Battle of Oriskany

In 1777 London conceive a bold plan to crush the rebellion by isolating New England who they perceived heart of the Patriot cause.8 The plan envisioned a three-pronged pincer movement converging on Albany, New York, seizing control of the vital Hudson River Valley.6 General John Burgoyne would lead the main army south from Canada down Lake Champlain.6 General William Howe was expected, at least by Burgoyne, to drive north from New York City up the Hudson.6

The third prong, a crucial supporting expedition, was assigned to Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger(SIL-in-jer). His mission was to advance east from Lake Ontario, moving down the Mohawk Valley.6 and proceeding to Albany to link up with Burgoyne and Howe.6

The Mohawk Valley itself was a rich heartland of New York, a vital artery for trade and travel. It was home to a complex tapestry of peoples. Prosperous colonial farms dotted the landscape.2 It was also the ancestral homeland of the powerful Haudenosaunee (Hoe-dee-no-SHAW-nee), the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy of Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga (Oh-nuhn-DAW-guh), Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora.3 For generations, tensions had festered here – old prejudices, bitter land disputes, struggles for political power and commerce.3 The American Revolution did not ignite these fires; it fanned them into a brutal inferno. Here, the war for independence became a vicious civil war, pitting neighbor against neighbor, brother against brother, and tragically, nation against nation within the Iroquois Confederacy itself.3

The stage was set and Fort Stanwix which was recently repaired and garrisoned by American troops under Colonel Peter Gansevoort(Ganz-vort), stood as the focal point. For it guarded the Oneida Carrying Place. An important portage linking the Atlantic with the interior of the county. So in July of 1777 St. Leger’s (SIL-in-jer) forces found themselves besieging Fort Stanwix. Word of the siege of reached Brigadier General Nicholas Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) via his Oneida allies.2 On July 30th, Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) issued a call-to-arms for the Tryon County Militia.2 By August 4th, roughly 800 militiamen, had answered the summons from their farms across the valley. They assembled at Fort Dayton (near modern Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer), NY).4 Here They were joined by their contingent of 60 to 100 Oneida allies. The combined force began its march westward along the Mohawk River Valley road, aiming to break the siege.2

By the evening of August 5th, Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)'s column made camp near the small Oneida village of Oriska (Oh-RIS-kuh) (modern Oriskany Oh-RIS-kuh-nee). They were now only six to eight miles east of the besieged Fort Stanwix.16 Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) dispatched three messengers to slip through the enemy lines and reach Colonel Gansevoort (Ganz-vort) inside the fort with his plans of attack.12 His plan involved the militia halting their advance until they heard three cannon shots from Fort Stanwix. This signal would indicate that Colonel Gansevoort was launching an attack on the British. Upon hearing the signal, Herkimer's militia would then attack the British from their position, effectively trapping the enemy between the militia and the fort's sortie in a "hammer-and-anvil" maneuver.

However, the messengers faced difficulty penetrating the siege lines and were delayed in reaching Gansevoort (Ganz-vort).12 As the morning of August 6th wore on, impatience grew among Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)'s subordinate officers34 Waiting near the enemy, with no signal forthcoming, they began to challenge Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)'s leadership.27 Tempers flared. Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) was accused of cowardice, even of harboring Loyalist sympathies – a particularly stinging charge, as his own brother, Johan Jost Herkimer (YO-hahn YOHST HER-kuh-mer), was indeed serving with St. Leger's (SIL-in-jers)forces.4

Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer), known for his normally cautious nature 38, was deeply affected by these accusations. His pride wounded, his own temper ignited, he made a fateful decision. Against his better judgment and abandoning his original plan, he angrily ordered the militia column to advance immediately, without waiting for the signal from the fort.27

Unbeknownst to Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer), his movements were already known to the enemy. St. Leger had been alerted to the militia's approach on August 5th, likely through intelligence provided by Mohawk scouts.27 This timely intelligence allowed the British to react swiftly. St. Leger immediately dispatched a strong detachment specifically to intercept and ambush the American relief column before it could reach the fort.8

The British commanders selected their ambush site with care.14 They chose a deep, swampy ravine located about six miles east of Fort Stanwix and just west of Oriskany Creek, where the rough military road descended steeply, crossed a marshy bottom via a causeway, and climbed the opposite slope.2 The terrain was ideal for concealment. Sir John Johnson positioned his Loyalist Royal Yorkers behind a rise at the western end of the ravine to block the head of the American column. John Butler's Rangers and the hundreds of Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga warriors under Brant concealed themselves in the thick woods lining both sides of the ravine.12 Brant's Mohawks were assigned to strike the rear of the column once it was fully inside the trap.27 The ambush was perfectly prepared, awaiting the unsuspecting militia.

Around ten o'clock on the humid morning of August 6, 1777, the vanguard of the Tryon County Militia marched into the waiting jaws of the trap.8 Critically, Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) had neglected to deploy scouts or flankers, a basic precaution when moving through potentially hostile territory. The long column, with General Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) riding near the front 12 and the slow-moving supply wagons trailing behind 27, descended into the gloomy ravine.

The British plan called for Johnson's Loyalists to engage the head of the column first, bottling up the Americans before the Indigenous warriors swept in from the flanks and rear. However, the plan went awry. Before the entire militia column had entered the ravine, the concealed warriors could no longer restrain themselves. The signal was given and a devastating volley erupted from the trees.2

The surprise was absolute; the effect was catastrophic.2 The militia, caught completely unaware in the constricted terrain, were thrown into instant chaos. Colonel Ebenezer Cox, commanding the 1st Regiment at the head of the column, was shot from his horse and killed in the first hail of bullets.2 General Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)’s horse was struck and killed, collapsing and trapping the General beneath it. A musket ball shattered Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)'s lower left leg.4

At the rear of the column, the men of the 3rd Regiment under Colonel Visscher (VISS-ker), many of whom had not yet entered the ravine, were struck by panic when the attack began.27 They broke and fled eastward, away from the carnage.2 Exultant warriors pursued the fleeing militiamen, cutting them down along the road for miles.2 In these first chaotic minutes, roughly half of Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)'s force was killed, wounded, or scattered in flight.12

That still left hundreds of militiamen trapped within the ravine, the battle instantly became a desperate, swirling melee.2 It was not a battle of orderly lines and volleys, but a brutal, close-quarters struggle for survival. Tomahawks, knives, bayonets, and clubbed muskets became the primary weapons.6 The fighting was intensely personal, fueled by the pre-existing hatreds of the Mohawk Valley civil war. Former neighbors recognized each other across the battlefield. Finding themselves locked in mortal combat. Brother fought against brother in the bloody confines of the ravine.3

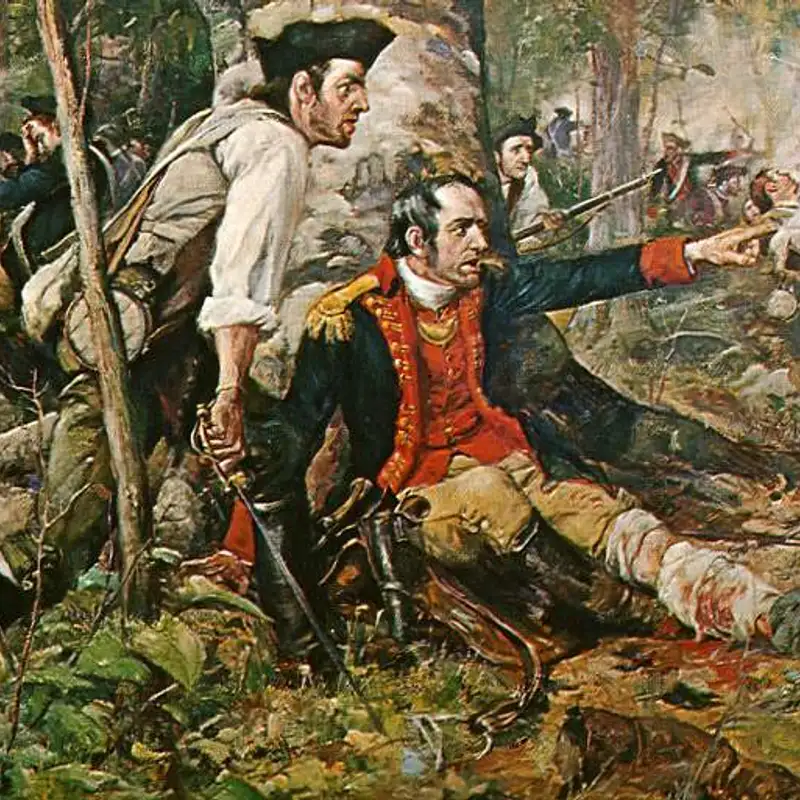

Amidst the terrifying chaos and carnage of the initial ambush, the leadership of Brigadier General Nicholas Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) proved decisive. Though suffering from a grievous wound, his leg shattered below the knee 4, he refused his officers' pleas to retire to the rear.12 Instead, he directed his men to carry him to the base of a large beech tree on the slight rise west of the ravine floor. There, they propped him up on his saddle. Calmly lighting his pipe, Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer), despite the agony of his wound, began to direct the defense, becoming a visible symbol of resolve in the face of disaster.4

Inspired by their commander's extraordinary courage and fighting for their very lives, the trapped militiamen and their Oneida allies began to regain some semblance of order. They fought their way out of the marshy bottom of the ravine, consolidating their position on the higher ground to the west.2 Here, they managed to form a rough defensive perimeter sheltering behind trees and rocks.8 For the next hour, this desperate band of militia and Oneida warriors held off the furious attacks of the Loyalists and their Iroquois allies.8

Around eleven o'clock that morning, nature intervened. The humid, oppressive air broke as a violent summer thunderstorm swept over the battlefield.2 Torrential rain lashed down, soaking the combatants and rendering the flintlock muskets temporarily useless as powder pans became wet.8 The intense downpour forced an unwilling pause in the fighting, lasting for about an hour.2

General Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) used this unexpected respite wisely. Observing the effectiveness of the Iroquois tactic of rushing individual militiamen with tomahawks while they struggled with the slow reloading process, he ordered a tactical shift.2 During the lull, he instructed his men to reorganize and fight in pairs. One man would fire while his partner held his fire and reloaded, ready to defend the pair. This simple but effective field expedient, tailored to the specific threat and his troops' capabilities, aimed to ensure that one weapon was always loaded, significantly reducing their vulnerability to close-quarters attacks during the reloading cycle.2

Meanwhile, the British forces also used the break. Sir John Johnson, perhaps concerned by the unexpected tenacity of the trapped militia, rode back to St. Leger's main camp near Fort Stanwix to request reinforcements. He returned with 70 additional men from his Royal Yorkers.23 John Butler, commander of the Rangers, interrogated some of the captured militiamen during the storm and learned of Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)'s plan to wait for a three-cannon signal from the fort.2 Seizing on this, Butler devised a ruse. He persuaded the newly arrived Royal Yorkers to turn their green uniform coats inside out, exposing the white or drab linings 37, in an attempt to make them resemble American troops arriving as a relief party from the direction of Fort Stanwix.2

As the storm subsided and the rain lessened, the fighting resumed. The disguised Loyalists advanced towards the American perimeter. The deception nearly succeeded, but the intimate nature of this civil conflict proved its undoing. Patriot Captain Jacob Gardinier (GAR-din-eer) peered closely at the approaching troops and suddenly recognized the face of one of his Loyalist neighbors among them.2 Shouting a warning, Gardinier (GAR-din-eer) and his men opened fire. The ruse collapsed, and the brutal, close-range fighting erupted once more, neighbor against neighbor, with renewed ferocity.2

While the desperate struggle raged in the Oriskany ravine, events were unfolding back at Fort Stanwix that would have a direct impact on the battle. Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)'s messengers, after their perilous journey through the enemy lines, finally reached the fort around 11:00 AM, delivering the news of the militia's approach and the ongoing engagement.2

Colonel Peter Gansevoort (Ganzvort) immediately acted on Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer)'s request for a diversionary attack. He ordered his second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Marinus Willett, to lead a sortie against the besiegers' camps.2 As the thunderstorm began to clear, Willett mustered 250 men along with a small, light 3-pounder cannon.2

Charging out of the fort's main gate, Willett's force headed towards the main Loyalist and Indigenous encampments located south and east of the fort, near the Mohawk River landings.2 Willett specifically targeted these camps based on prior scouting reports from Oneida allies operating out of the fort.30 With most of the warriors and Loyalists engaged miles away at Oriskany, the camps were nearly deserted. The few remaining guards were quickly overwhelmed and fled towards the main British camp further north.23

Willett's men then proceeded to thoroughly loot and destroy the enemy encampments.12 They gathered a significant amount of spoils, destroying what they couldn't carry. Critically, they also seized Sir John Johnson's personal baggage, which contained his letters, campaign plans, and the regiment's orderly book.19 Several prisoners were captured.30

As Willett prepared to return to the fort, St. Leger (SIL-in-jer) hastily assembled troops from the main British camp in an attempt to cut off the American raiding party.25 However, Willett effectively used his 3-pounder cannon, along with covering fire from the fort's artillery, to disrupt the British formation and deter an attack. Willett and his men marched back into Fort Stanwix triumphantly, having executed the raid "without the loss of a single man".25

The sortie was a stunning success. It provided a significant morale boost to the besieged garrison, who now also possessed valuable intelligence gleaned from the captured documents and prisoners regarding the enemy's strength and intentions.30 More importantly, the raid had a direct impact on the battle still raging miles away at Oriskany (Oh-RIS-kuh-nee).

Willett's attack on the camps eventually reached the ears of the combatants at Oriskany (Oh-RIS-kuh-nee) relayed by frantic messengers. For the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga (Oh-nuhn-DAW-guh) warriors fighting alongside the Loyalists, the news that their camps – containing their provisions, spare clothing, personal belongings, and family members – were being raided was alarming.12 Already discouraged by the unexpectedly fierce resistance of the militia and the mounting casualties among their own ranks27, their enthusiasm for the fight evaporated. Protecting their possessions and families became their immediate priority. They began to disengage from the battle and stream back towards the besieged fort.7

With the abrupt departure of their crucial Indigenous allies, the remaining Loyalist and British forces under Sir John Johnson and John Butler found their position untenable. They too were forced to break off the engagement and withdraw from the battlefield.8 The Battle of Oriskany (Oh-RIS-kuh-nee), after roughly six hours of savage fighting, sputtered to an end.8

On the American side, the surviving Tryon County militia were exhausted, traumatized, and severely depleted. They had held their ground against overwhelming odds after the initial shock, but they were in no condition to press on towards Fort Stanwix. Their objective of relieving the fort had failed. Their focus shifted to survival and evacuating the wounded. They gathered as many injured comrades as they could, including their gravely wounded commander, General Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer), and began the sorrowful retreat eastward, back towards the relative safety of Fort Dayton.2

Casualties

American casualties were horrendous of the

800 + 60-100 Indians (385+ killed, 50+ wounded, 30+ captured / missing)

One analysis calculated that 55% of the militiamen who marched with Herkimer (HER-kuh-mer) were killed in the battle, an almost unparalleled fatality rate for an American force during the war.

The stark ratio of killed to wounded (roughly 385 killed vs. 50 wounded in one estimate 29) illustrates the brutal nature of the close-quarters fighting and the lack of mercy shown. The impact on Tryon County was immense; nearly every community felt the loss. The Tryon County Militia Brigade was effectively shattered as a fighting force for the remainder of the war.27

British

500-700 :

Regulars who tried to stop Willet (7 killed, 21 wounded)

Loyalists ( handful )

Indians (60-150 casualties) up to 150 casulaties

100-150+ casualties

For the Iroquois people, it marked the horrific moment their centuries-old Confederacy turned upon itself, forever remembered in their oral traditions as A Place of Great Sadness.2

The heavy losses inflicted on St. Leger's Indigenous allies, coupled with the psychological blow of Willett's raid, severely damaged the cohesion and morale of the besieging force.2 But still the siege continued.